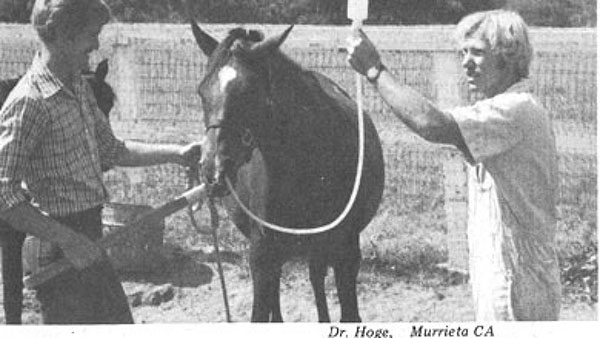

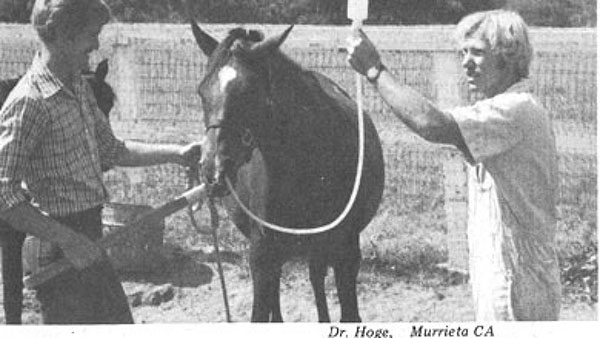

May/June 1981 issue of Horse Illustrated A vet administering anthelmintic drugs via nasogastric tube.

a three-part series on worms and horses

May/June 1981

issue of Horse Illustrated A vet administering anthelmintic drugs via

nasogastric tube.

The following is the second of a three-part series on worms and horses, co-authored by Ellen Collinson and Alex Wilson. You can find the article in it’s entirety, as well as other articles and information on iridology, herbs, and nutrition for horses on *Ellen’s website.

|

1. The History of Worming The approach to worming has changed over the years and, at the University of Kentucky, Gene Lyons PhD, Sharon Tolliver BS and Hal Drudge DVM documented the history of worming in the scientific journal Veterinary Parasitology. Their paper threw up some unusual practices. In the 17th century there was a notion that drawing blood from a horse and getting the horse to drink its own blood was a very good way to kill worms and to cure other equine ailments. How a horse was made to drink its own blood was not described. Other historical ways to resolve worms were equally bizarre and included soap, liquorice, linseed oil, chick or human feces, eggs, guts of chicken or pigeons, and, worst of all, mercury. Owners were advised against using some of these methods with pregnant mares. Feeding horses tobacco was also practiced, but the amount needed to have any effect would more than likely make a horse quite ill. Also many people experimented with herbs without proper knowledge of herbal medicine and so rarely getting the required results. However, today’s leading herbal products are very carefully formulated and trialled to ensure the best possible results. In April 1891 the first edition of the book Veterinary Country Practice was printed. Written by “Qualified and Experienced Members of the Royal College of Veterinary Surgeons”, it was written expressly for Chemists and Druggists. In this book there were several recipes for worming, some containing small quantities of Arsenic, also herbs, including Aloes, Ginger, Liquorice, Valerian and Garlic; also used were Linseed oil, Turpentine, Gentian and this list goes on. There were 11 different recipes, showing that even in the 1890s they knew that it was beneficial to change the treatment to combat resistance. It has to be said it was also to give the less well-off a chance to use cheaper ingredients. The last edition was reprinted in November 1935. Carbon tetrachloride, best known as a component that is used in dry cleaning, was one of the first chemicals used for worming. Whilst it was semi-effective, it was as one can imagine, very toxic to horses. The 1940s marked the start of a new era of chemical wormers, but even the early chemicals that were introduced, like phenothiazine, were very toxic. Phenothiazine was, however, the first product that would start to attack the strongyles, which until then were a major issue for horses and their owners. But by the 1960s, both in the UK and the USA there was evidence to show that these parasites were starting to become resistant to chemical worming, a situation that was going to make chemical worming a major problem from there on in. The 1950s saw the introduction of some products that seemed to be effective on a number of different parasites; mixing a number of chemicals together in smaller qualities helped combat the toxicity of a large dose of one product. This cocktail had to be administered by a vet by inserting a tube down the horse’s throat, a maneuver which also carried risks. Organophosphates, which were commonly used in sheep dip, were popular in the 1970s. They are very toxic chemicals both to horses and to humans who get in contact with with. Today there are some farmers who used these chemicals in sheep dips, etc., who are suffering from multiple chemical poisoning; in some cases, they are totally house-bound and cannot live normal lives.

It wasn’t until the 1970s when owners were able to worm their horses themselves without the need to call in the vet to run tubes down a horse’s throat. New products were being marketed as a paste and the first of these was Benzimadazole. This drug had a much larger margin for error and could be administered in much smaller quantities than previous de- worming chemicals. Many drugs from this family of chemicals are still in circulation today. Also in the 1970s Pyrantel was also offered from an alternative family of chemicals. This proved to be very popular when parasites started to get resistant to the benzimadazole products. In the 1980s Ivermectin was introduced which allegedly kills the larvae of parasites as well as the adults and this product would prove to be very popular with horse owners, especially as it could also be administered as a paste. Finally, in the 1990s we saw the introduction of Moxidectin, marketed on the basis of it being able to kill the pesky small strongyles in the intestines of the horse.

2. Parasites’ resistance to chemical wormers Whilst the drug companies would want you to believe that theirs is the answer to exterminating parasites in horses, there is a fundamental problem that exists – resistance. Parasites have had to learn to survive and to adapt to their environments and in doing so they have managed to find ways to adapt to modern chemicals that are meant to stop their reproduction. This is called resistance and these worms are now passing this resistance on to their offspring. There is no single chemical product on the market that stops the resistant parasites and there is evidence to show that the number of resistant parasites is on the increase. Historically it has been believed that rotating the products and using wormers from different chemical families can eliminate most resistant parasites but in a paper published by Blanek, Brady, Nichols, Hutchinson et al. in which extensive studies were conducted in the USA using quarter horses, they concluded that resistance in equine parasites was an ever-increasing problem and that more research needed to be done into rotating wormers. Another problem that blanket rotation needs to consider is the fact that certain classes of drugs are aimed at different families of parasites and unless the horse owner is aware of which parasites their horses carry, they can be using chemicals that can have little or no effect on their horse or horses. One solution to this problem is to have regular egg counts utilising the dung of the horse. This, however can be costly and very few owners undertake this kind of interest in their horses’ worm problems. The usual thinking is that by carrying out regular worming on their animals that will be sufficient. Another approach that should be considered is using a herbal product as an alternative. There seems little evidence that there are worms that become resistant to the tried and tested herbal products. More details of herbal worming will be discussed later.

3. Toxic effects of chemical wormers The one subject that will never have been discussed by the manufacturers of the main brands of wormers is the potential side effects of using chemicals. As has been discussed above, these products are poisonous to worms and unless they are used very carefully, they can equally be poisons for horses. As the resistance to chemicals grows, so stronger dosages need to be used and the safety margins become smaller. The following side effects can be caused by the use of equine wormers: swollen glands, colic, allergies, laminitis, intestinal problems, skin reactions, drooling, hoof problems, internal problems, plus dangers to the horse’s immune system. Let’s face it, horses are not designed to be filled with toxic chemicals!

A good example is toxic hepatitis, which is caused by

substances poisonous to the liver. There are three known

sources: chemical poisons, plant poisons and metabolic

poisons. Chemical poisons include arsenic, copper, mercury

and phosphorous among others. It should be noted that

tetrachlorethylene and carbon tetrachloride, both used as

worming agents, are potential causes of non-infectious,

toxic hepatitis, when improperly used. In addition, there is the environmental impact of these chemicals. Using these wormers mean that these chemicals get into the earth through horses’ urine and feces. The bigger picture means that other animals, especially wildlife, agricultural animals and pets will be affected. It has been noted that birds that eat horse droppings from chemically treated horses die. These chemicals stay in the land for over three years and can also find their way into streams and rivers, affecting fish, and they can also get into our drinking water. We have a responsibility to our environment not to pollute it unnecessarily.

Part 3 of this series, will discuss herbal options.

Credits |

Do you

have a topic you would like to see here or article you'd like to submit?

Please

E-mail me

We wish to thank all of the people that have shared their experiences &

knowledge with others by sending us tips and donating articles. For articles on

our pages that have been reproduced, credit is given and a link is posted to

your site (reproducing articles archives information on our server which

decreases broken links that occur when content on the site was either removed or

relocated without proper redirects in place to lead visitors to the correct

page.)

Please forgive us if we did not give full credit for any one of the wonderful articles

here. If we have used something of yours

that you would like removed please let me know.

All rights reserved. No part of any pages may be reproduced in any form or

means without written permission of Lil Beginnings Miniature Horses.

Lil Beginnings Miniature Horses is not responsible for any death, injuries, loss, or other damages which may result from the use of the information in

our pages.